Before she does so, she grimly assesses her soon-to-be lover’s wife:

In The Rules of Engagement (2003), the unhappily married narrator, Elizabeth Wetherall, embarks on an affair with her older, undesirable husband’s charismatic friend. In any case, their marriages and invariably privileged lives are never in jeopardy. Cheated-on wives, in her portrayal, are too self-centered, ruthless, and confident to warrant our compassion. Literature from the point of view of “the other woman” is rare, and she is the genre’s subversive maestro. If Austen popularized the marriage plot, Brookner upended it, immersing us in the emotionally clandestine lives of mistresses and other romantic misfits.

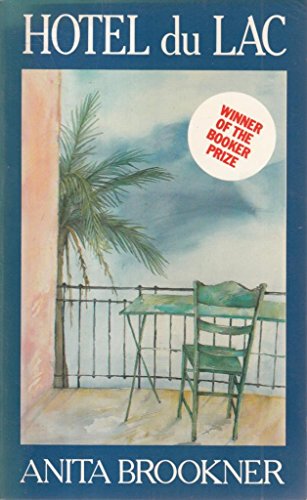

The novelist Tessa Hadley admitted in the Guardian that before reading her, “I’d expected something ladylike, lavender-scented, prissy and precious I knew as soon as I opened my eyes to her words that this writing was everything opposite to that.” On a recent episode of the Backlisted podcast, the literary critic and Brookner convert Lucy Scholes said, “For many years, I labored under that rather stupid impression that she wrote novels about spinsters in the worst possible shape and form a spinster can take.” It didn’t help that Publishers Weekly, in 1990, described Brookner as “a latter-day Jane Austen,” a label oft repeated despite its almost comical inaccuracy. Over the course of several decades and an astonishing twenty-four novels, including the Booker Prize–winning Hotel du Lac, the prevailing myth held that Brookner wrote conservative, middlebrow stories about dull and repressed women. The British novelist Anita Brookner, who died last year at age eighty-seven, suffered from the most misleading of literary reputations.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)